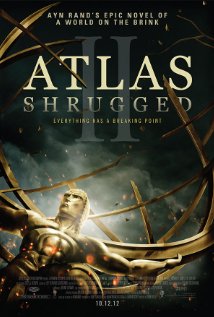

Why Ayn Rand Won’t Go Away

Atlas Shrugged, Part 2

and the Motor of Moral Psychology

This article was originally published on HuffingtonPost.com on October 12, 2012

After seeing the Los Angles premiere of Atlas Shrugged, Part 2, the film that opened October 12 based on the 1957 novel by Ayn Rand (and with an entirely new cast and higher production values a vast improvement over Part 1), a question struck me as I was exiting the theater surrounded by Hollywood types most commonly stereotyped as liberal: Why don’t liberals admire Ayn Rand and her philosophy of objectivism, so forcefully presented in this book and film?

It is not a mystery that the woman who called herself a “radical for capitalism” would be embraced by some conservatives such as Paul Ryan and Ron Paul, but why do liberals not recognize that Rand was also a champion of individual rights, was outspoken against racism, bigotry and discrimination against minorities, and most notably was ahead of her time in championing women’s rights and demonstrating through her novels (and films) that women are as smart as men, as tough-minded as men, as hard working as men, as ambitious as men, and can even run an industrial enterprise as good as—if not better than—men? In the teeth of a 2010 study that revealed Hollywood still discriminates against women when it comes to roles in films, most notably the number and length of speaking parts and the continued blatant sexuality in which women show far more skin than men but speak far less, the hero of Atlas Shrugged, Dagny Taggert (played by Samantha Mathis in the new film), has the most speaking roles (and shows almost no skin), runs her own transcontinental railroad, handles with ease both seasoned male politicians and hard-nosed male titans of industry, and embodies courage and character deserving of respect and admiration from women and men, liberals and conservatives.

An answer may be found in the fact that American politics is a duopoly of those who tend toward being either fiscally and socially liberal or fiscally and socially conservative. Rand’s fiscal conservatism and social liberalism fits into neither camp comfortably (and is mostly commonly associated with the Libertarian party). As well, the moral psychology behind the political duopoly leads people to either believe that moral principles are absolute and universal or that they are relative and cultural. Rand’s implacable absolutism on moral issues, especially her seemingly cold-hearted fiscal conservatism, more comfortably fits into the conservative camp, but even there only barely.

Consider a few correlations from my dataset of 34,371 Americans who took “The Morality Survey” (you can take it yourself), constructed by myself and U.C. Berkeley social scientist Frank Sulloway and analyzed by my graduate students Anondah Saide and Kevin McCaffree: (1) We found a significant correlation (r=.29) between social conservatism and the belief that moral principles are absolute and universal (and between social liberalism and the belief that moral principles are relative and cultural), so Rand’s philosophy does not match that of most Americans. (2) We found a significant correlation (r=.24) between fiscal conservatism and the belief that moral principles are absolute and universal (and the reverse for social liberalism), so fiscal liberals will not embrace Rand here. We also found a correlation (r=.27) between belief in God and belief that moral principles are absolute and universal, and here again Rand is an outlier as an atheist who firmly believed in absolute and universal moral principles (discoverable through reason, she believed). So for liberals, Rand’s fiscal conservatism and moral principle absolutism trumps her social liberalism, and even for many on the right her atheism and rejection of faith calls into question her conservative bona fides.

Our duopolistic political system also explains why third parties in American politics—from libertarians and tea partyers to progressives and green partyers—cannot get a toehold. Despite Romney’s 47% gaffe, in point of fact both candidates know that each will automatically receive about that percentage of the vote, leaving the final 6% up for grabs. Why are we so politically divided? One answer comes from the 19th century political philosopher John Stuart Mill: “A party of order or stability, and a party of progress or reform, are both necessary elements of a healthy state of political life.”

But why would our political life be so configured? A deep evolutionary answer may be found in the moral psychologist Jonathan Haidt’s new book The Righteous Mind, in which he argues that, to both liberals and conservatives, members of the other party are not just wrong; they are righteously wrong. Their errors are not just factual, but intentional, and their intentions are not just misguided, but dangerous. As Haidt explains, “Our righteous minds made it possible for human beings to produce large cooperative groups, tribes, and nations without the glue of kinship. But at the same time, our righteous minds guarantee that our cooperative groups will always be cursed by moralistic strife.” Thus, he concludes, morality binds us together into cohesive groups but blinds us to the ideas and intentions of those in other groups.

Third parties and outliers like Rand fall into neither group and so are not even taken seriously. But why only two parties? According to Haidt, the answer is in our moral psychology and how liberals and conservatives differ in their emphasis on five moral foundations:

- Harm/care, which underlies such moral virtues as kindness and nurturance;

- Fairness/reciprocity, which leads to such political ideals of justice, rights, and individual autonomy;

- Ingroup/loyalty, which creates within a tribe a “band-of-brothers” effect and underlies such virtues as patriotism;

- Authority/respect, which lies beneath such virtues as esteem for law and order and respect for traditions; and

- Purity/sanctity, which emphasizes the belief that the body is a temple that can be desecrated by immoral activities.

Sampling hundreds of thousands of people Haidt found that liberals are higher than conservatives on 1 and 2 (Harm/care and Fairness/reciprocity), but lower than conservatives on 3, 4, and 5 (Ingroup/loyalty, Authority/respect, and Purity/sanctity), while conservatives are roughly equal on all five dimensions, although slightly higher on 3, 4, and 5 (you can take the survey).

Obama’s emphasis on caring for the poor and fairness across all socioeconomic classes appeals to liberals, whereas conservatives are drawn toward Romney’s reinforcement of faith, family, nation, and tradition. Libertarians split the difference in being fiscally conservative and socially liberal, but their one-dimensional emphasis on individual freedom above all else (as in Rand’s philosophy) leaves them devoid of political support.

So when you see Atlas Shrugged, Part 2, remember that this is far more than a film or a story about a railroad and a mysterious motor. It is a vehicle to get us to think about which moral principles we value the most, because as Ayn Rand believed, it is ideas that move the world.