Positive Psychopathy

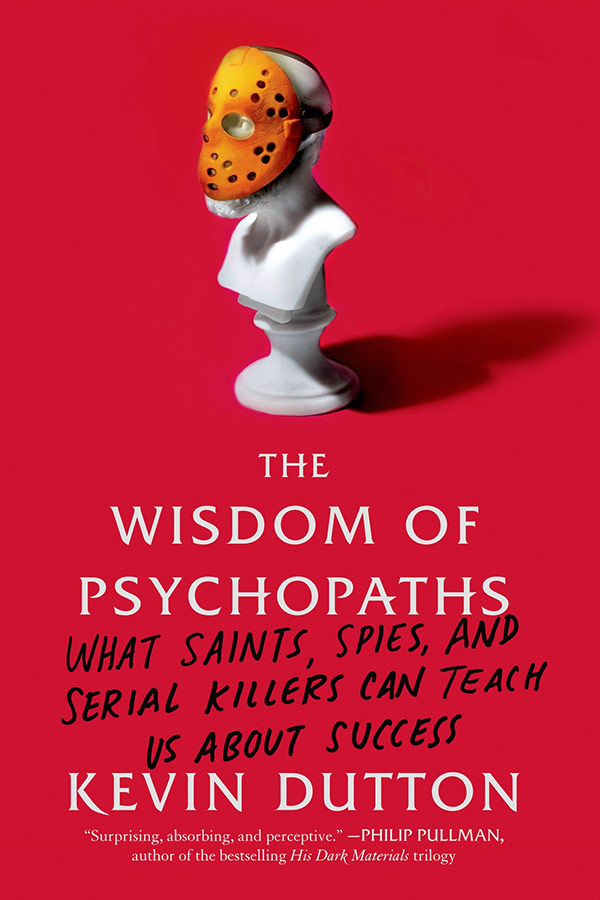

A review of The Wisdom of Psychopaths: What Saints, Spies, and Serial Killers Can Teach Us About Success by Kevin Dutton. A a version of this review was published in the Wall Street Journal on November 6, 2012 under the title “When Madness Pays Off”.

In one of her standup comedy routines Ellen Degeneres riffs on those commercials for depression medications that begin “Do you ever feel sad?”, to which Degeneres responds sardonically, “Yes, I’m alive!”

The problem with all diagnostic tools is that they attempt to squeeze into a well-defined box symptoms or characteristics that are often fuzzy, ill-defined, context dependent, and on some level a part of daily life, so the criteria lists grows and the diagnostic labels broaden into spectrums. Everyone occasionally feels sad, so some depression might indeed be considered part and parcel of living. Recent research suggests, for example, that mild depression may be one way of coping with a bad situation that, like pain, is a signal to make a change. But as it ratchets up in intensity to the point of causing dysfunction, then depression may indeed be a diagnosis in need of a treatment. Autism is another example, with the “autism spectrum” ranging from barely functional children requiring full-time care to the famous author Temple Grandin, who earned a Ph.D. in animal science and was ranked by Time magazine as one of the 100 most influential people in the world. A single word fails to capture the spread.

“Psychopathy” suffers the same problem. Psychopathy is a spectrum personality disorder characterized by callousness, antisocial behavior, superficial charm, narcissism, grandiosity, a sense of entitlement, a lack of empathy and remorse, and poor impulse control and criminality. A slate of publications on psychopathy over the past two decades—from Robert Hare’s path-breaking 1991 book Without Conscience to Simon Baron Cohen’s 2011 The Science of Evil—reveal that about 1–3 percent of men in the general population are psychopaths, and that about half of all violent criminals in prison have been diagnosed as psychopathic. Indeed, psychopathy is almost always associated with criminals and serial killers, but as the University of Cambridge research psychologist Kevin Dutton argues in The Wisdom of Psychopaths, within psychopathy there are shades of grey, from one end of the spectrum inhabited by CEOs, lawyers, salesmen, Wall Street Traders, and tough-minded bosses who enjoy growling “You’re fired!”, to the other end inhabited by the likes of Ted Bundy who, after raping and murdering 35 women in the 1970s, boasted “I’m the coldest son of a bitch you’ll ever meet.”

In 1980 the psychologist Robert Hare developed the Psychopathy Checklist (PCL) of 20 items with a maximum score of 40 (on each of the 20 items you can score a 0, 1, or 2). A revised version of the scale is still in use today (PCL-R) and you can take different versions of it yourself Online (not advised). I scored a 7. The beginning level for psychopathy is at 27. It’s a spectrum. In many circumstances, such as in business, sports, and other competitive enterprises, it’s good to be a little charming, tough-minded, socially manipulative, impulsive, and to have a need for stimulation when you find yourself bored with flat emotional affect. But as these personality traits scale up to the point where a little charm becomes manipulative conning, where self-confidence escalates to grandiosity, where occasional exaggeration morphs into pathological lying, where tough-mindedness devolves into cruelty, where impulsivity becomes irresponsibility, and especially if all of these characteristics lead to criminal behavior, we have the makings of a dangerous psychopath.

The Psychopathic Personality Inventory (PPI) developed by the psychologist Scott Lilienfeld consists of a much wider swath of personality dimensions measured by 187 questions, factor analyzed into a cluster of combined characteristics, such as Machiavellian Egocentricity, Impulsive Nonconformity, Blame Externalization, Carefree Nonplanfulness, and the like. The idea is to recognize the fact that most of us have most of these personality traits in some measure. As Lilienfeld told Dutton in an interview, “You and I could post the same overall score on the PPI. Yet our profiles with regard to the eight constituent dimensions could be completely different. You might be high on Carefree Nonplanfulness and correspondingly low on Coldheartedness, whereas for me it might be the opposite.” Context matters. It’s perfectly normal for vacations to be carefree and unplanned. And you should release the coldhearted hounds when someone is trying to con you or when a telemarketer phones your home at 9 pm.

The Wisdom of Psychopaths is an engaging and enlightening look at both the positive and negative sides of the personality characteristics that make up the diagnosis of psychopathy, but what Dutton really brings to the table is a self-reflective look at what it means to be fully human with both good and evil capacities. He develops a skill set he calls the Seven Deadly Wins, “seven core principles of psychopathy that, apportioned judiciously and applied with due care and attention, can help us get exactly what we want; can help us respond, rather than react, to the challenges of modern-day living; can transform our outlook from victim to victor, but without turning us into a villain.” The seven are: Ruthlessness, Charm, Focus, Mental toughness, Fearlessness, Mindfulness, and Action. I’m not sure about the first one (“hardheadedness” sounds less Machiavellian than ruthlessness), but bearing in mind that these are words that translate into behavior, the idea is that if you want to accomplish something (anything) in life you need a certain amount of all these traits, but not too much. “Cranking up the ruthlessness, mental toughness, and action dials, for instance, might make you more assertive—might earn you more respect among your work colleagues,” Dutton explains. “But ratchet them up too high and you risk morphing into a tyrant.”

Or consider the anatomy of a hero, which Dutton does in his evaluation of the Stanford University social psychologist Philip Zimbardo’s Heroic Imagination Project, in which the famed author of one of the best treatises’ on evil ever penned (The Lucifer Effect) followed up with a study of what makes people good: “The decision to act heroically is a choice that many of us will be called upon to make at some point in our lives,” Zimbardo explains to Dutton. “It means not being afraid of what others might think. It means not being afraid of the fallout for ourselves. It means not being afraid of putting our necks on the line.”

Perhaps we need another word—another label—for the positive side of psychopathy, the side of the spectrum where those personality dimensions are put to good use and are used for good. Positive Psychopathy might work (with Negative Psychopathy as its antithesis). But whatever we call it we should always remember that human behavior is multivariate, complex, and context dependent and our labels do not always capture its rich tapestry.