Good Rules Make Good Capitalists, Part 1

As the SEC prepares its case against Goldman Sachs for allegedly intentionally defrauding the public with toxic securities that it created, sold, then bet against, I want to reflect for a moment on the need for rules in a free market society. Critics of capitalism believe that we libertarians want an essentially lawless society in which people are free to do whatever they want. That may be true for some libertarians, but I have come to believe through experience and science that free markets operate best within a system of clearly defined and strictly enforced rules and laws. Within the system itself markets should be as free as possible and people should be free to trade with whomever they want without interference from the state (think Chinese citizens trading ideas about democracy with each other and outsiders), but good rules make good capitalists.

Consider a sports analogy: In 1982, three other men and I founded the 3,000-mile nonstop transcontinental bicycle Race Across America (RAAM) from L.A. to New York, sponsored by Budweiser and televised on ABC’s Wide World of Sports. The rules were simple: each cyclist takes the same route, has a support vehicle and crew that follows behind providing food, drink, and equipment, and no drafting behind or hanging onto a vehicle is allowed. The race started on the Santa Monica Pier in California. The first cyclist to reach the Empire State Building in New York City would be declared the winner. That was the entire set of rules, which we didn’t even bother to write down.

All four of us finished the race and the next year dozens of cyclists wanted to compete so we began to outline some rules. During that first race, for example, it wasn’t clear what to do with a rider who went off course—can he get a ride in his support vehicle back to the route where he left it? (yes), can he be driven up the route the same distance he rode off course? (no). Although no drafting was allowed, it is often windy out on the open plains, and if there is a cross-wind from your left when your support vehicle comes alongside to hand off water bottles and food, there is a noticeable drafting effect. Not to mention that ten days is a long time to ride by yourself, so it is psychologically advantageous to have your support crew to talk to for long stretches. So we had to draft extensive rules defining how long a handoff can last (one minute), how many times an hour (four), with room for exceptions to the rule, such as if the temperature exceeds 100 degrees, in which case the number of handoffs is unrestricted.

Lon Haldeman & Jim Lampley, Empire State Building, 1982

Once you start writing down what people can and cannot do, the list grows exponentially. As the years moved on and the race grew in popularity, the rulebook expanded with it. Women entered in 1984, so we added rules about gender divisions. Cyclists over 50 and 60 years of age wanted to race, so we added rules about age divisions. Four-man relay teams entered in 1989, so we created a new set of rules just for them, that subsequently had to be expanded to encompass two-person relay teams, men-and-women relay teams, age division relay teams, and even corporate relay teams. Every year something would happen that led to more rules. In the 1989 race one of the competitors was riding slowly up the long grade of Oak Creek Canyon from Sedonna to Flagstaff, Arizona, with his two vans and motorhome all caravanning behind him, preventing cars from safely passing. This went on for miles until someone called the police, but by the time the officers arrived they could only find the next rider back, whom they stopped on the side of the road, thereby disrupting his pace and costing him time, which we had to subtract from his overall finishing time. Another year, also in Arizona, we had a similar problem on a busy stretch of Highway 89, after which someone called the Arizona Department of Transportation to complain, resulting in a post-race ruling by the DOT that RAAM could only pass through Arizona during the day. As this would have obviated the nonstop nature of the race, I had to negotiate a deal with the Arizona DOT with a proviso in the rules that read: “The Follow Vehicle may not impede following traffic for more than one minute. The Follow Vehicle must pull off the road and let traffic pass when five or more vehicles are waiting to pass regardless of time. During the day the rider may proceed alone, with the Follow Vehicle catching up once traffic is clear. At night the rider must also pull off the road.”

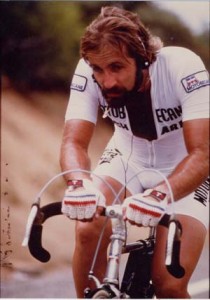

Shermer, 1982, listening on Sony Walkman (pre iPod)

One especially hot year one of the RAAM riders happened upon a small hotel pool while passing through a diminutive Western town, so he dismounted his bike and leaped into the pool, fully attired in cycling clothes, shoes, gloves, and helmet. Someone called the police, and once again by the time they arrived the pool perpetrator was gone, so they pulled over the next competitor that happened along, thereby disrupting his pace. This led to yet another rule, this one prohibiting competitors from swimming in public pools without permission from the owner. Most of the racers enjoy listening to music, either from small earbud phones or from speakers mounted on the roof of their following vehicle, which led to two additional problems: one, blasting music through tiny earphones jammed in your ears makes it difficult to hear oncoming traffic, ambulances, and the like; two, passing through small towns in the middle of the night blasting rock-n-roll music from loudspeakers tends to awaken the locals. Thus, two new rules were added, one restricting the use of only one earphone and the other curtailing the broadcasting of music during hours of darkness.

All of these new rules, of course, require the addition of appropriate punishments for violations, which we assessed in time penalties. However, an exhausted cyclist who is forced by an official to take time off the bike in the middle of the race may actually benefit from the penalty, so we had to write even more rules about where and when the penalties would be served, which we determined would be in a penalty “box” ten miles from the finish line (and, yes, we have had cyclists passed by competitors while sitting there on the side of the road). More rules and penalties mean more officials needed to assess them, and therefore more potential for subjective misjudgments on the part of officials (who are often sleep-deprived and exhausted themselves), so we had to add yet another set of rules that allow the cyclists to challenge the officials’ assessed penalties, and a set of guidelines for the Race Director to make a final evaluation before the end of the race if such a challenge is made, as well as a post-race board to hear one final appeal by the athlete if he or she feels that both the official and the Race Director made the wrong decision. Finally, we created a nonprofit governing body—the Ultra-Marathon Cycling Association (UMCA)—to oversee the entire sport, including and especially the development and adjudication of the rules.

The structure and development of this sporting event and the rules that govern it—as quotidian an example as it is—serves as an analogue for society at large. In its simplicity, sports can help clarify and illuminate the evolution and operations of more complex and nuanced social institutions. Just as good rules make good competitors, good walls make good neighbors and good laws make good citizens. People naturally want what is best for themselves, but most people also want what is fair for others. Without a structure in place to create and enforce firm and fair rules to meet both of these needs, people become more self-centered than other-centered, and if you go far enough down that path it degenerates into Hobbes’ bellum omnium contra omnes, “the war of all against all.”

Now, my libertarian friends, don’t panic thinking I’ve gone soft in the head liberal about creating obsessive government regulations in the economy. In this post I’ll demonstrate how industries naturally create their own set of rules from the bottom-up, and that these can serve as useful guidelines for top-down regulators.