Why the singular of “data” is not “anecdote”

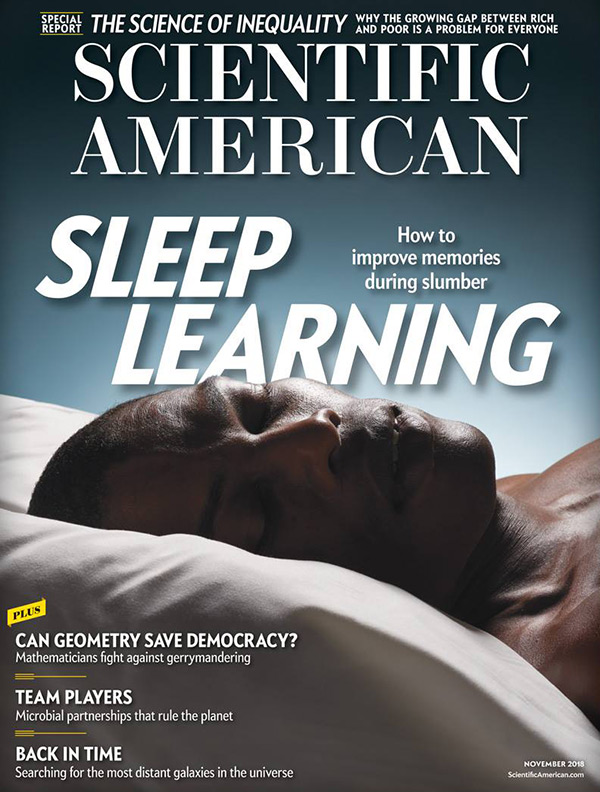

This column was first published in the November 2018 issue of Scientific American.

For a documentary on horror movies that seem cursed, I was recently asked to explain the allegedly spooky coincidences associated with some famous films. Months after the release of Poltergeist, for example, its 22-year-old star, Dominique Dunne, was murdered by her abusive ex-boyfriend; Julian Beck, who played the preacher “beast,” succumbed to stomach cancer before Poltergeist II’ s release; and 12-year-old Heather O’Rourke died months before the release of what would be her last starring role in Poltergeist III.

The Exorcist star Linda Blair hurt her back when she was thrown around on her bed when a piece of rigging broke; Ellen Burstyn was injured on set when flung to the ground; and actors Jack MacGowran and Vasiliki Maliaros both died while the film was in postproduction (their characters died in the film).

When Gregory Peck was on his way to London to make The Omen, his plane was struck by lightning, as was producer Mace Neufeld’s plane a few weeks later; Peck avoided aerial disaster again when he canceled another flight at the last moment (that plane crashed, killing everyone onboard); and two weeks after filming, an animal handler who worked on the set was eaten alive by a lion. (continue reading…)

read or write comments (3)

Why “outcasting” works better than violence

After binge-watching the 18-hour PBS documentary series The Vietnam War, by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, I was left emotionally emptied and ethically exhausted from seeing politicians in the throes of deception, self-deception and the sunk-cost bias that resulted in a body count totaling more than three million dead North and South Vietnamese civilians and soldiers, along with more than 58,000 American troops. With historical perspective, it is now evident to all but delusional ideologues that the war was an utter waste of human lives, economic resources, political capital and moral reserves. By the end, I concluded that war should be outlawed.

In point of fact, war was outlawed … in 1928. Say what?

In their history of how this happened, The Internationalists: How a Radical Plan to Outlaw War Remade the World (Simon & Schuster, 2017), Yale University legal scholars Oona A. Hathaway and Scott J. Shapiro begin with the contorted legal machinations of lawyers, legislators and politicians in the 17th century that made war, in the words of Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz, “the continuation of politics by other means.” Those means included a license to kill other people, take their stuff and occupy their land. Legally. How?

In 1625 the renowned Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius penned a hundreds-page-long treatise originating with an earlier, similarly long legal justification for his country’s capture of the Portuguese merchant ship Santa Catarina when those two countries were in conflict over trading routes. In short, The Law of War and Peace argued that if individuals have rights that can be defended through courts, then nations have rights that can be defended through war because there was no world court. (continue reading…)

read or write comments (18)

Why Freedom of Inquiry in Science and Politics is Inviolable

This article appeared in the Journal of Criminal Justice in May 2017.

In the 1990s I undertook an extensive analysis of the Holocaust and those who deny it that culminated in Denying History, a book I coauthored with Alex Grobman (Shermer & Grobman, 2000). Alex and I are both civil libertarians who believe strongly that the right to speak one’s mind is fundamental to a free society, so we were surprised to discover that Holocaust denial is primarily an American phenomenon for the simple reason that America is one of the few countries where it is legal to doubt the Holocaust. Legal? Where (and why) on Earth would it be illegal? In Canada, for starters, where there are “anti-hate” statutes and laws against spreading “false news” that have been applied to Holocaust deniers. In Austria it is a crime if a person “denies, grossly trivializes, approves or seeks to justify the national socialist genocide or other national socialist crimes against humanity.” In France it is illegal to challenge the existence of “crimes against humanity” as they were defined by the Military Tribunal at Nuremberg “or in connection with any crime within the jurisdiction of the Tribunal, whether or not in violation of the domestic law of the country where perpetrated.” The “Race Relations Act” in Great Britain forbids racially charged speech “not only when it is likely to lead to violence, but generally, on the grounds that members of minority races should be protected from racial insults.” Switzerland, Belgium, Israel, Italy, New Zealand, and Sweden have all passed similar laws (Douglas, 1996). In 1989 the New South Wales parliament in Australia passed the “Anti-Discrimination Act” that includes these chilling passages, Orwellian in their implications: (continue reading…)

Comments Off on Giving the Devil His Due

Then ideology needs to give way

Ever since college I have been a libertarian—socially liberal and fiscally conservative. I believe in individual liberty and personal responsibility. I also believe in science as the greatest instrument ever devised for understanding the world. So what happens when these two principles are in conflict? My libertarian beliefs have not always served me well. Like most people who hold strong ideological convictions, I find that, too often, my beliefs trump the scientific facts. This is called motivated reasoning, in which our brain reasons our way to supporting what we want to be true. Knowing about the existence of motivated reasoning, however, can help us overcome it when it is at odds with evidence.

Take gun control. I always accepted the libertarian position of minimum regulation in the sale and use of firearms because I placed guns under the beneficial rubric of minimal restrictions on individuals. Then I read the science on guns and homicides, suicides and accidental shootings (summarized in my May column) and realized that the freedom for me to swing my arms ends at your nose. The libertarian belief in the rule of law and a potent police and military to protect our rights won’t work if the citizens of a nation are better armed but have no training and few restraints. Although the data to convince me that we need some gun-control measures were there all along, I had ignored them because they didn’t fit my creed. In several recent debates with economist John R. Lott, Jr., author of More Guns, Less Crime, I saw a reflection of my former self in the cherry picking and data mining of studies to suit ideological convictions. We all do it, and when the science is complicated, the confirmation bias (a type of motivated reasoning) that directs the mind to seek and find confirming facts and ignore disconfirming evidence kicks in. (continue reading…)

read or write comments (43)

Has there ever been a time when the political process has been so bipartisan and divisive? Yes, actually, one has only to recall the rancorousness of the Bush-Gore or Bush-Kerry campaigns, harken back to the acrimonious campaigns of Nixon or Johnson, read historical accounts of the political carnage of both pre- and post-Civil War elections, or watch HBO’s John Adams series to relive in full period costuming the bipartite bitterness between the parties of Adams and Jefferson to realize just how myopic is our perspective.

We can go back even further into our ancestral past to understand why the political process is so tribal. But for the business attire donned in the marbled halls of congress we are a scant few steps removed from the bands and tribes of our hunter-gatherer ancestors, and a few more leaps afield from the hominid ancestors roaming together in small bands on the African savannah. There, in those long-gone millennia, were formed the family ties and social bonds that enabled our survival among predators who were faster, stronger, and deadlier than us. Unwavering loyalty to your fellow tribesmen was a signal that they could count on you when needed. Undying friendship with those in your group meant that they would reciprocate when the chips were down. Within-group amity was insurance against the between-group enmity that characterized our ancestral past. As Ben Franklin admonished his fellow revolutionaries, we must all hang together or we will surely hang separately.

In this historical trajectory our group psychology evolved and along with it a propensity for xenophobia—in-group good, out-group bad. Thus it is that members of the other political party are not just wrong—they are evil and dangerous. Stray too far from the dogma of your own party and you risk being perceived as an outsider, an Other we may not be able to trust. Consistency in your beliefs is a signal to your fellow group members that you are not a wishy-washy, Namby Pamby, flip-flopper, and that I can count on you when needed. (continue reading…)

Comments Off on Paleolithic Politics