On July 26 I had a nasty cycling crash. I’m fond of telling people that cycling is a low-impact sport, unless you impact the ground, which I did that day. My cycling buddy Bob McGlashan were riding the Lake Casitas loop from Summerland, down the coast to Ventura (there’s a nice bike path next to the 101 freeway) and up the road paralleling highway 33 north. We had a howling tailwind and were flying at over 20mph on a modest upgrade. Well, at the big left turn to the lake, a car was coming the other way at high speed, so I timed my left turn to be after he flew past me, but at the last minute he hit the brakes and turned right. I had to veer right around him a little, which would have been fine, but as his car passed in front of me there was a pothole I had to swerve right to miss, sending me straight into the curb, which I hit at around 20mph, flipping me right into a dirt/rock field. I slammed my head, shoulder and hip really hard, the same side as my total hip replacement from 2013. There’s a dent in my helmet from a rock, so it did its job, but I could barely walk. As we were too far from home for a call to my wife, and no Ubers anywhere near us, I tried riding and there was almost no pain at all, so we rode the two hours back to the car. But by the time I got home I couldn’t walk from my car to the house without assistance, so I went to the Cottage Hospital ER and got an X-Ray and then a CT scan. There were two small pelvic fractures, one on the inferior ramps of the pelvic bone (not a problem) but the other one is on the acetabulum of the hip where the ball of the joint presses up against the socket (mine is titanium and plastic), so every time I put weight on the leg it hurt like hell.

I also pinched a nerve in my neck, which two days later was unbearably painful. I couldn’t sleep without strong painkillers. Another cycling partner of mine, Dr. Walter Burnham, happens to be a world-class orthopedic surgeon specializing in the spine, so he did an MRI on my neck and found some pretty severe degeneration of C-5, 6, and 7—not from the crash but from…”life” (he said, when I asked). So that led to the ACDF surgery, which Walt did on September 6, two days before my 65th birthday.

I would have done it earlier, but Medicare coverage started for me on September 1 so I had to wait in order to have the surgery fully covered. Yes, I have health insurances, with Blue Shield, and a fairly expensive plan at that, but even so my share of what would have been owed without Medicare would have been over $10,000. So, it was worth waiting a couple of weeks. I could rant for pages more about our messed up healthcare system, but I won’t as at the moment I am grateful for the near miraculous performance of Dr. Walt and his team, along with everyone else who took care of me along the way. (i.e., it’s the system that’s messed up, not the people.)

I did notice how careful everyone is now with opioid painkillers, which saved me from being miserable for weeks. When the ER docs wrote a script for a codeine painkiller, unbeknownst to me the law now requires that any opioid prescription must include a prescription for Naloxone, the inhaler that saves your life if you overdose. The codeine (Tylenol 3) was $1.57 for 12 pills. The Naloxone was $75. My wife Jennifer picked up the order for me. I called the ER to complain about the price differential. The woman explained the law to me. I told her I understood, but asked “the instructions say to take 1 every 4 hours. What moron would take all 12 at once?” She replied: “you’d be surprised.” Alas, that’s the world we live in now.

Comments Off on Anterior Cervical Discectomy & Fusion (ACDF)

or, My Big Bike Crash and Surgical Adventure

Audible Inc., the world’s largest producer and provider of downloadable audiobooks and other spoken-word entertainment, in conjunction with The Great Courses, is creating audio-only, non-fiction content for Audible’s millions of listeners. The first three titles include Dr. Michael Shermer’s new and original course on: Conspiracies & Conspiracy Theories: What We Should Believe and Why.

Order today

Watch Dr. Shermer’s introduction

Brief Course Description

What is the difference between a conspiracy and a conspiracy theory? Who is most likely to believe in conspiracies, and why do so many people believe them? Is there some test of truth we can apply when we hear about a conspiracy that can help us determine if the theory about it is true or false? In this myth-shattering course, world-renowned skeptic and bestselling author Dr. Michael Shermer tackles history’s greatest and widespread conspiracy theories, carefully deconstructing them on the basis of the available evidence. In the current climate of fake news, alternative facts, and the rise of conspiracy theories to national prominence and political influence it is time to consider how to distinguish true conspiracies (Lincoln’s assassination, the Pentagon Papers, Watergate) from false conspiracy theories (Sandy Hook, 9/11, fake moon landing). You learn how conspiracies arise, what evidence is used to support them, and how they hold up in the harsh light of true historical, even scientific analysis, as well as why people believe them. Illuminating and compelling, the next time you hear someone talking about a conspiracy theory, this course just may give you the detective skills to parse the truth of the claim.

Conspiracies & Conspiracy Theories consists of 12 lectures, 30-minutes each.

PART I: Conspiracies & Why People Believe Them

-

The Difference Between Conspiracies and Conspiracy Theories

-

Classifying Conspiracies and Characterizing Believers

-

Why People Believe in Conspiracy Theories

-

Cognitive Biases and Conspiracy Theories

-

Conspiracy Insanity

-

Constructive Conspiracism

PART II: Conspiracy Theories & How to Think About Them

-

The Conspiracy Detection Kit

-

Truthers and Birthers: The 9/11 and Obama Conspiracy Theories

-

The JFK Assassination: The Mother of All Conspiracy Theories

-

Real Conspiracies: What if They Really Are Out to Get You?

-

The Deadliest Conspiracy Theory in History

-

The Real X-Files: Conspiracy Theories in Myth and Reality

Bonus Lecture: Letters from Conspiracists

Order today

Watch Dr. Shermer’s introduction

About Michael Shermer

Dr. Michael Shermer is the Publisher of Skeptic magazine, a Presidential Fellow at Chapman University, the host of the Science Salon podcast, and for 18 years a monthly columnist for Scientific American. He is the author of a number of New York Times bestselling books including: Heavens on Earth, The Moral Arc, The Believing Brain, Why People Believe Weird Things, Why Darwin Matters, The Mind of the Market, How We Believe, and The Science of Good and Evil. His two TED talks, viewed nearly 10 million times, were voted in the top 100 of the more than 2000 TED talks. Dr. Shermer received his B.A. in psychology from Pepperdine University, M.A. in experimental psychology from California State University, Fullerton, and his Ph.D. in the history of science from Claremont Graduate University.

View all titles by Michael Shermer on Audible.com.

You play a vital part in our commitment to promote science and reason. If you enjoy the content Michael Shermer produces, please show your support by making a donation, or by becoming a patron.

Comments Off on Conspiracies & Conspiracy Theories:

What We Should and Shouldn’t Believe—and Why

The case for scientific humanism

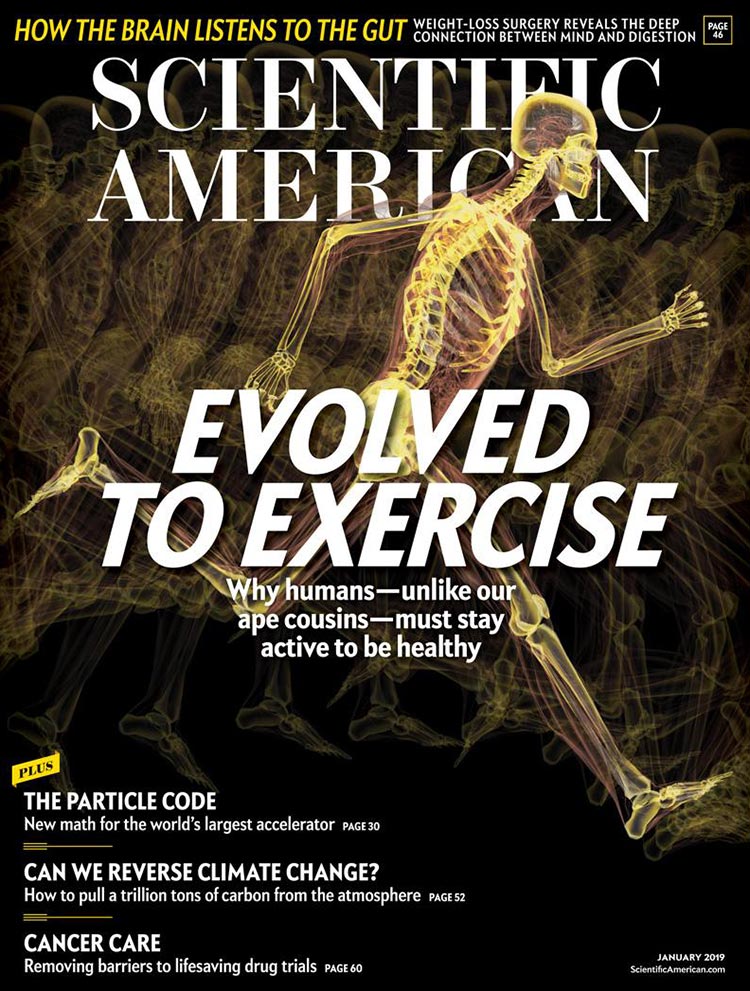

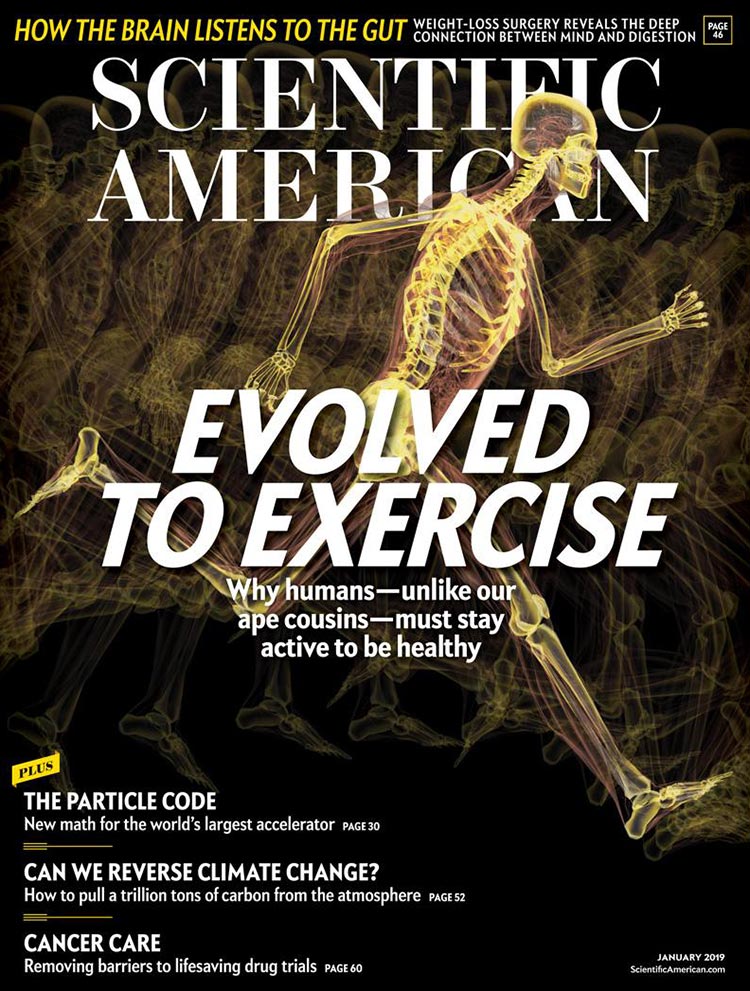

This column was first published in the January 2019 issue of Scientific American.

In the April 2001 issue of Scientific American, I began this column with an entry entitled “Colorful Pebbles and Darwin’s Dictum,” inspired by the British naturalist’s remark that “all observation must be for or against some view, if it is to be of any service.” Charles Darwin penned this comment in a letter addressing those critics who accused him of being too theoretical in his 1859 book On the Origin of Species. They insisted that he should just let the facts speak for themselves. Darwin knew that science is an exquisite blend of data and theory. To these I add a third leg to the science stool—communication. If we cannot clearly convey our ideas to others, data and theory lie dormant.

For 214 consecutive months now, I have tried to communicate my own and others’ thoughts about the data and theory of science as clearly as I am able. But in accordance with (Herb) Stein’s Law—that things that can’t go on forever won’t—this column is ending as the magazine redesigns, a necessary strategy in the evolution of this national treasure, going on 174 years of continuous publication. I am honored to have shared a fleeting moment of that long history, grateful to the editors, artists and production talent for every month I was allowed to share my views with you. I will continue doing so elsewhere until my own tenure on this provisional proscenium ends (another instantiation of Stein’s Law)—many years in the future, nature and chance willing— so permit me to reflect on what I think science brings to the human project of which we are all a part.

Modern science arose in the 16th and 17th centuries following the Scientific Revolution and the adoption of scientific naturalism— the belief that the world is governed by natural laws and forces that are knowable, that all phenomena are part of nature and can be explained by natural causes, and that human cognitive, social and moral phenomena are no less a part of that comprehensible world. In the 18th century the application of scientific naturalism to the understanding and solving of human and social problems led to the widespread embrace of Enlightenment humanism, a cosmopolitan worldview that esteems science and reason, eschews magic and the supernatural, rejects dogma and authority, and seeks to understand how the world works. Much follows. Most of it good.

Human progress, which has been breathtaking over the past two centuries in nearly every realm of life, has principally been the result of the application of scientific naturalism to solving problems, from engineering bridges and eradicating diseases to extending life spans and establishing rights. This blending of scientific naturalism and Enlightenment humanism should have a name. Call it “scientific humanism.”

It wasn’t obvious that the earth goes around the sun, that blood circulates throughout the body, that vaccines inoculate against disease. But because these things are true and because Nicolaus Copernicus, William Harvey and Edward Jenner made careful measurements and observations, they could hardly have found something else. So it was inevitable that social scientists would discover that people universally seek freedom. It was also inevitable that political scientists would discover that democracies produce better lives for citizens than autocracies, economists that market economies generate greater wealth than command economies, sociologists that capital punishment does not reduce rates of homicide. And it was inevitable that all of us would discover that life is better than death, health better than illness, satiation better than hunger, happiness better than depression, wealth better than poverty, freedom better than slavery and sovereignty better than suppression.

Where do these values exist to be discovered by science? In nature—human nature. That is, we can build a moral system of scientific humanism through the study of what it is that most conscious creatures want. How far can this worldview take us? Does Stein’s Law apply to science and progress? Will the upward bending arcs of knowledge and wellbeing reach a fixed upper ceiling?

Remember Davies’s Corollary to Stein’s Law—that things that can’t go on forever can go on much longer than you think. Science and progress are asymptotic curves reaching ever upward but never touching omniscience or omnibenevolence. The goal of scientific humanism is not utopia but protopia—incremental improvements in understanding and beneficence as we move ever further into the open-ended frontiers of knowledge and wisdom. Per aspera ad astra.

read or write comments (1)