The Rules of Capitalism, Part 3

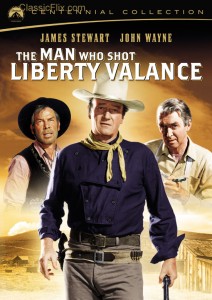

Liberty and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.

This is the third essay in a series on the relationship between rules, freedom, and prosperity.

Read part 1 on Skepticblog.org and part 2 over at True/Slant.

I believe that the following commentary on the necessity of law and order has some bearing on what is unfolding in Arizona—when the rules are not clearly written or consistently enforced, people will take the law into their own hands because society cannot run smoothly without law and order.

In Part 3 in my essay series on the relationship between rules, freedom, and prosperity, I want to turn to one of my favorite films, John Ford’s 1962 classic, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, in which a clash of moralities unfolds in the wild-west frontier town of Shinbone, Arizona. There in the dusty streets and ramshackle buildings two self-contained and self-consistent moral codes come into conflict. One moral code is the Cowboy Ethic, where trust is established through courage, loyalty, and personal allegiance to friends and family, and where disputes are settled and justice is served between individuals who have taken the law into their own hands. The other moral code is the Law Ethic, where trust is established through the transparent and mutually-agreed upon rule of law, and where disputes are settled and justice is served between all members of the society who, by virtue of living there, have tacitly agreed to obey the rules. Only one of these moral codes can prevail.

In The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, the Cowboy Ethic is represented by two people, one good and the other evil. John Wayne’s character, Tom Doniphon, is a fiercely loyal and deeply honest gunslinger duty-bound to enforce justice on his own terms through the power of his presence backed by the gun on his hip. Lee Marvin’s title character, Liberty Valance, is a coarse and unkempt highwayman whose unruly behavior provokes fights with the locals, most of whom fear and loathe him.

The Law Ethic is represented by Jimmy Stewart’s character, Ransom Stoddard, an attorney hell bent on seeing his beloved Shinbone make the transition from cowboy justice to the rule of law. Employing the commonly-used flashback technique, John Ford opens his film at the end of the story with the funeral of Tom Doniphon, which is attended by an elderly Stoddard swamped by reporters inquiring why the now-distinguished U.S. Senator would bother returning to his native town just to be present at the memorial services of a down-and-out gunfighter.

When they were younger and coming of age in this western territory just slightly out of reach of the long arm of the law, Stoddard and Doniphon were of radically different minds when it came to how justice should be served, each believing that the other’s strategy is either outdated (Doniphon’s gun) or naïve (Stoddard’s law). Despite this difference, or perhaps because of it, they become faithful friends, both believing that in the end justice must prevail. When Liberty Valance arrives on the scene it is clear that he respects only one man, Tom Doniphon, because they share the Cowboy Ethic that men settle their disputes honorably between themselves. As Doniphon boasted, “Liberty Valance is the toughest man south of the Picketwire—next to me.” But Valance’s disdain for the milksop Stoddard and his naïve notions about the effectiveness of the law knows no bounds. Entering a restaurant where Stoddard is dining, for example, Valance berates him, taunts him, and finally trips the waiter, sending Stoddard’s dinner to the floor. As Stoddard meekly tries to avoid a confrontation, Doniphon enters and stares down Valance, who snaps back, “you lookin’ for trouble, Doniphon?” In his inimitable John Wayne drawl, Doniphon responds, “You aimin’ to help me find some?” Valance caves to Doniphon’s challenge and scurries out of the restaurant. “Well now; what do you supposed caused him to leave?” Doniphon wonders rhetorically. The sardonic response from a patron in reference to the impotency of Stoddard’s philosophy reveals which ethic is still dominant: “Why it was the specter of law and order rising from the gravy and the mashed potatoes.”

Despite Valance’s constant taunting, Stoddard holds to his belief that until Valance is caught doing something illegal there can be no justice. When Doniphon tells Stoddard “You better start pack’n a handgun,” Stoddard rejoins, “I don’t want to kill him. I just want to put him in jail.” At long last, however, Stoddard can take the derision no more, so he decides to take Doniphon’s advice that “out here a man settles his own problems,” and turns to him for gun-fighting lessons. When Valance challenges Stoddard to a dual, the overconfident naïf accepts and a late-night showdown ensues. In a darkened street, the two men square off. Stoddard is trembling in fear while Valance mocks and scorns him, shooting first too high and then too low. When Valance takes aim to kill, Stoddard shakily draws his weapon and discharges it. Valance collapses in a heap. Having felled one of the toughest guns in the west Stoddard goes on to become a local hero, building that image into political capital and working his way up from local politics to a distinguished career as a United States Senator. It appears that the Law Ethic prevailed over the Cowboy Ethic.

Not so fast. The man who shot Liberty Valance was Tom Doniphon. Knowing that Stoddard was no match for Valance, in a replay of the dual we see Doniphon lurking in the shadows and fingering a rifle, which he engaged to kill Valance at the crucially-timed moment when the two men drew their weapons. Holding to the cowboy ethic of loyalty and friendship, Doniphon takes the secret to his grave, where at the end of the story Stoddard is now paying his respect. When Stoddard finally reveals to a newspaper reporter the truth about who really shot Liberty Valance, the paper decides not to print the truth because, in what has become one of the most memorable lines in filmic history, “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

Despite this being a typical shoot-em-up western film, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance contains many moral subtleties. The philosopher Patrick Grim, who called my attention to the film as a tale of moral conflict, notes that both Stoddard and Doniphon violated their principles, but they did so because this was the only means by which one moral code could displace the other. By agreeing to a dual with Valance, Stoddard adopted a form of conflict resolution that he previously deemed illegal and immoral, and after discovering the truth about who really shot Liberty Valance, he chose to live a lie of omission then capitalized on his unearned heroism. For his part, Doniphon violated his moral code by ambushing Valance from the shadows instead of facing him man to man in the street, and then hiding the truth about what really happened, thereby tacitly endorsing Stoddard’s faux use of the Cowboy Ethic in order to help bring about the Law Ethic. In fact, both men violated both codes of morality, and with ample irony the only person who did not violate his moral code was the scurrilous Liberty Valance. But in the end, as Shinbone grew in size the transition from one moral code to the other had to happen, and in this moral homily it was friendship and loyalty that facilitated the change. It was the psychology of trust between individuals that enabled a society of trust among the collective to come to fruition.

The fictional Shinbone embodies any small community in transition from an informal to a formal moral code and system of justice. As long as population numbers are low and everyone in a community is either related to one another or knows one another through regular interactions, the code of the cowboy can work relatively well to keep the peace and ensure trust and social stability. But when communities expand and population numbers increase, the opportunities for unchecked violations of such informal codes expands exponentially, requiring the creation of such social technologies as codes, courts, and constitutions.

Continue reading part 4 over at True/Slant.