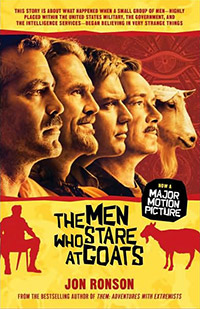

Staring at Men Who Stare at Goats

The Men Who Stare at Goats had so much potential as a film given the bizarre and comical nature of the weird things the United States government believed about the paranormal in its two-decade long secret psychic spy program, so wonderfully captured by the British investigative journalist John Ronson in his book of the same title. Give Hollywood some credit for at least keeping his book title (a rarity indeed in Hollywood because, you know, producers and directors always know what’s best for your book). Unfortunately, if you saw the trailer for the film, you saw most of the funniest bits, with only a few more gems scattered throughout. This is a shame because with four major stars in the film it could have done much better than the $13.3 million it grossed in its opening weekend. This was slightly better than the UFO thriller The Fourth Kind ($12.5 million), and Paranormal Activity ($8.6 million), although the latter film was produced for about $15,000 and has accumulated a staggering 45-day gross of $97.4 million, empirical evidence that the paranormal still pays, and pays very well!

At the very end of the credits of The Men Who Stare at Goats, as Boston’s foot-stomping song “More Than a Feeling” blasts along, a disclaimer rolls by at eye-blurring speed, basically saying that most of the characters and plot line in the film are entirely made up and have next to no connection to Ronson’s book or what really happened in the psychic spy program. Ain’t that the truth. The premise is so contrived as to be almost painful (if only it were funny, which it wasn’t): the wife of Ewan McGregor’s journalist character leaves him for his senior editor, a one-armed creepo with a black handed prosthetic that was apparently attractive to the smitten wife, and so he sets out to prove his journalistic/husbandly manhood by trying to get embedded in the U.S. army during the Iraqi invasion. Along the way he runs into George Clooney’s army psychic spy character and gets pulled into doing a story about what the U.S. government did back in the 1970s and 1980s. The bit about men staring at goats to try to kill them is true. The part about playing the theme song from Barney the purple dinosaur as a torture weapon is also true. The army officer who tried to run through walls also happened, with precisely the same result as in the movie: the wall’s atoms repelled his atoms with the predictable result. (And why, oh why, would they not use the real name of that officer: Major General Albert Stubblebine III? You couldn’t make up a better name!) I think that’s about it. Oh, guys did wear their hair longer then and had mustaches.

It is with some irony, then, that at the beginning of the film a line appears: “More of this is true than you would believe.” Okay, so what is true and what isn’t? Here is what I know. In 1995, the story broke that for the previous 25 years the U.S. Army had invested $20 million in a highly secret psychic spy program called Star Gate (also Grill Flame and Scanate), a Cold War project intended to close the “psi gap” (the psychic equivalent of the missile gap) between the United States and Soviet Union. The Soviets were training psychic spies, so we would as well. Forget the film. Read the book. In The Men Who Stare at Goats Jon Ronson tells the story of this program, how it started, the bizarre twists and turns it took, and how its legacy carries on today.

In a highly readable narrative style, Ronson takes readers on a Looking Glass-like tour of what U.S. Psychological Operations (PsyOps) forces were researching: invisibility, levitation, telekinesis, walking through walls, and even killing goats just by staring at them (the ultimate goal was killing enemy soldiers telepathically). In one project, psychic spies attempted to use “remote viewing” to identify the location of missile silos, submarines, POWs, and MIAs from a small room in a run-down Maryland building. If these skills could be honed and combined, perhaps military officials could zap remotely viewed enemy missiles in their silos, or so the thinking went.

Initially, the Star Gate story received broad media attention — including a spot on ABC’s Nightline — and made a few of the psychic spies, such as Ed Dames and Joe McMoneagle, minor celebrities. As regular guests on Art Bell’s pro-paranormal radio talk show, the former spies spun tales that, had they not been documented elsewhere, would have seemed like the ramblings of paranoid cultists.

But Ronson has brought new depth to the account by carefully tracking down leads, revealing connections, and uncovering previously undisclosed stories. For example, Ronson convincingly connects some of the bizarre torture techniques used on prisoners at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, and Iraq’s Abu Ghraib prison, with similar techniques employed during the FBI siege of the Branch Davidians in Waco, Texas. FBI agents blasted the Branch Davidians all night with such obnoxious sounds as screaming rabbits, crying seagulls, dentist drills, and Nancy Sinatra’s “These Boots Are Made for Walking.” The U.S. military employed the same technique on Iraqi prisoners of war, instead using the theme song from the PBS kids series Barney and Friends — a tune many parents concur does become torturous with repetition.

One of Ronson’s sources, none other than Uri Geller (of bent-spoon fame), led him to one Maj. Gen. Albert Stubblebine III, who directed the psychic spy network from his office in Arlington, Virginia. Stubblebine thought that with enough practice he could learn to walk through walls, a belief encouraged by Lt. Col. Jim Channon, a Vietnam vet whose post-war experiences at such new age meccas as the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California, led him to found the “first earth battalion” of “warrior monks” and “jedi knights.” These warriors, according to Channon, would transform the nature of war by entering hostile lands with “sparkly eyes,” marching to the mantra of “om,” and presenting the enemy with “automatic hugs.” Disillusioned by the ugly carnage of modern war, Channon envisioned a battalion armory of machines that would produce “discordant sounds” (Nancy and Barney?) and “psycho-electric” guns that would shoot “positive energy” at enemy soldiers.

Although Ronson expresses skepticism throughout his narrative, he avoids the ontological question of whether any of these claims have any basis in reality. That is, can anyone levitate, turn invisible, walk through walls, or remote view a hidden object? Inquiring minds (scientists) want to know. The answer is an unequivocal no. Under controlled conditions remote viewers have never succeeded in finding a hidden target with greater accuracy than random guessing. The occasional successes you hear about are due either to chance or suspect experiment conditions, like when the person who subjectively assesses whether the remote viewer’s narrative description seems to match the target already knows the target location and its characteristics. When both the experimenter and the remote viewer are blinded to the target, all psychic powers vanish.

Herein lies an important lesson that I have learned in many years of paranormal investigations and that Ronson gleaned in researching his illuminating book: What people remember rarely corresponds to what actually happened. Case in point to return to the title theme: A man named Guy Savelli told Ronson that he had seen soldiers kill goats by staring at them, and that he himself had also done so. But as the story unfolds we discover that Savelli is recalling, years later, what he remembers about a particular “experiment” with 30 numbered goats. Savelli randomly chose goat number 16 and gave it his best death stare. But he couldn’t concentrate that day, so he quit the experiment, only to be told later that goat number 17 had died. End of story. No autopsy or explanation of the cause of death. No information about how much time had elapsed; the conditions, like temperature, of the room into which the 30 goats had been placed; how long they had been there, and so forth. Since Ronson was skeptical, Savelli triumphantly produced a videotape of another experiment where someone else supposedly stopped the heart of a goat. But the tape showed only a goat whose heart rate dropped from 65 to 55 beats per minute.

That was the extent of the empirical evidence of goat killing, and as someone who has spent decades in the same fruitless pursuit of phantom goats, I conclude that the evidence for the paranormal in general doesn’t get much better than this.

They shoot horses, don’t they?

• FOLLOW MICHAEL SHERMER ON TWITTER •