The Other ‘L’ Word: Why I am a Libertarian

In a nutshell, I am a libertarian because conservatives are a bunch of gun-totting, Hummer-driving, hard-drinking, Bible-thumping, black-and-white-thinking, fist-pounding, shoe-stomping, morally-hypocritical blowhards, and liberals are a bunch of tree-hugging, whale-saving, hybrid-driving, sandle-wearing, bottled-water-drinking, ACLU-supporting, flip-flopping, wishy-washy, Namby Pamby bedwetters. There’s a better way. Libertarianism.

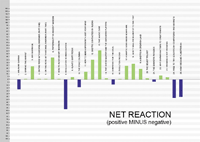

Michael Shermer’s recent Skepticblog posts about libertarianism have drawn an enormous volume of commentary. To better assess the tone of the comments, Junior Skeptic editor Daniel Loxton sat down with Skepticblog webmaster William Bull to undertake an informal content analysis for internal review.

This was a lengthy, brute-force task. All of Michael Shermer’s posts were parceled out to a team of volunteers (one reviewer per thread) who read every single comment — and assigned each of those thousands of comments a positive, neutral, or negative rating based on simple guidelines (“NEUTRAL: Too close to call, a non-sequitur, or expresses something not directly related to the topic of the author’s post”).

Individual commenters were allowed only one unique “vote” per thread.

The results of this back-of-the-envelope analysis (current to May 8th) are presented below, along with Dr. Shermer’s thanks for the constructive comments.

Okay, now that I have your attention, let me address the constructive comments posted in response to last week’s blog post on how I became a libertarian, and this week explain why. But first, what is a libertarian? I hate labels, and as you can see from the comments people make certain assumptions based on the label instead of the person and particular beliefs. Nevertheless, labels are cognitive shortcuts, so the shortest thumbnail is this: a libertarian is socially liberal and fiscally conservative. It’s an alternative to the standard left-right linear spectrum, and it allows one to nuance positions on different issues. For example, I am pro-choice, pro gay marriage, and pro separation of church and state, which makes me a card-carrying liberal, right? Well, I am also in favor of lower taxes, cutting welfare programs, privatizing social security, and replacing the income tax with either a flat tax or abolishing it altogether and replacing it with a national income tax, which makes me a card-carrying conservative, right? So what am I?

(Parenthetically, I find it troubling that most atheists, agnostics, skeptics, free thinkers, humanists and secular humanists are liberal. The reason I find this troubling is not because I am not a liberal (although as noted above, I agree with liberals on many issues), but because most people think that the skeptical/humanist movement is (or should be) politically neutral. If it were, there would be roughly a 50/50 split of liberals and conservatives. But it isn’t, and I think that’s a problem. Humanists, for example, are supposed to be in favor of all humans, but when virtually our entire constituency votes Democratic, that means we are missing half the human population! There’s something wrong with this picture. I’m not saying that we should all be libertarians; only that a more politically diversified membership would indicate that our movement is more politically balanced. When I point out this discrepancy to my liberal friends and colleagues, they predictably explain the left-leaning bias as due to the fact that liberals are right! Of course… My conservative friends say the same thing when I note the conservative bias in businesses and commerce related organizations.)

Basically, libertarians are for freedom and liberty for individuals, and we prefer not to have the state involved in either our bedrooms or our boardrooms. This is not a simple hedonistic “I want to move to Idaho and smoke pot and watch porn and the rest of you all be damned” (although I’m sure there are libertarians who want precisely this). Rather, libertarianism is based on the principle that individuals should be free to choose for themselves. Libertarianism is grounded in the Principle of Freedom: All people are free to think, believe, and act as they choose, as long as they do not infringe on the equal freedom of others.

There is a very simple reason why libertarians do not like government: it is not just that government is so inefficient (although it is), or that it elevates graft and corruption to new levels of bureaucratic efficiency (although it does), or that it treats its citizens like we’re a bunch of juvenile helpless pinhead morons in need of a nanny to take care of us from womb to tomb (we aren’t and we don’t); it is because it infringes on our freedoms to choose.

Of course, the devil is in the details of what constitutes “infringement,” but as I outlined in The Mind of the Market, there are at least a dozen essentials to freedom:

- The rule of law.

- Property rights.

- Economic stability through a secure and trustworthy banking and monetary system.

- A reliable infrastructure and the freedom to move about the country.

- Freedom of speech and the press.

- Freedom of association.

- Mass education.

- Protection of civil liberties.

- A robust military for protection of our liberties from attacks by other states.

- A potent police force for protection of our freedoms from attacks by other people within the state.

- A viable legislative system for establishing fair and just laws.

- An effective judicial system for the equitable enforcement of those fair and just laws.

Under our current system of politics government clearly has a role in most (but not all) of these 12, but only in the capacity of what we might call Preventative Rights: preventing others from infringing on our freedoms (taking my property, preventing me from speaking or writing or associating, inhibiting my freedom to exchange with others on a voluntary basis, etc.). By contrast, government should not be in the business of Providing Rights: providing goods and services that require the infringement of our freedoms (e.g., taking my property through taxes to pay for someone else’s education, health care, vacations, paternity leaves, etc.).

Basically I believe in individual choice and responsibility. You make your choices and you are responsible for the consequences of those choices. Of course, we are not just individuals living in isolation; we are spouses and significant others, we are members of families and extended families, we are constituents of social communities, and we are citizens of societies. As such, we have a moral obligation to take care of those who cannot take care of themselves (children, the elderly, the infirm), to help those who cannot help themselves (the mentally ill, severely handicapped), and to give aid and comfort to victims of natural disasters and totalitarian regimes, but through private choice and charity.

It is none of the government’s business who I choose to help and give aid and charity to, and I find it deeply morally repugnant that bureaucratic agencies have the legal right to confiscate my wealth through force or the threat of force (taxes), launder my money and waste most of it to run the government organizations that process my money (with dollops allocated for paying for bridges to nowhere and prostitutes for politicians), and redistribute it to people who I do not know. Libertarians are not uncharitable selfish hedonists; we just want the freedom to choose.

Okay, I know, you’re all sick of hearing about the other “L Word,” so for next week’s blog I’ll write about my experiences at the Thinking Digital conference in Newcastle Upon Tyne, the UK’s version of TED.