The case for scientific humanism

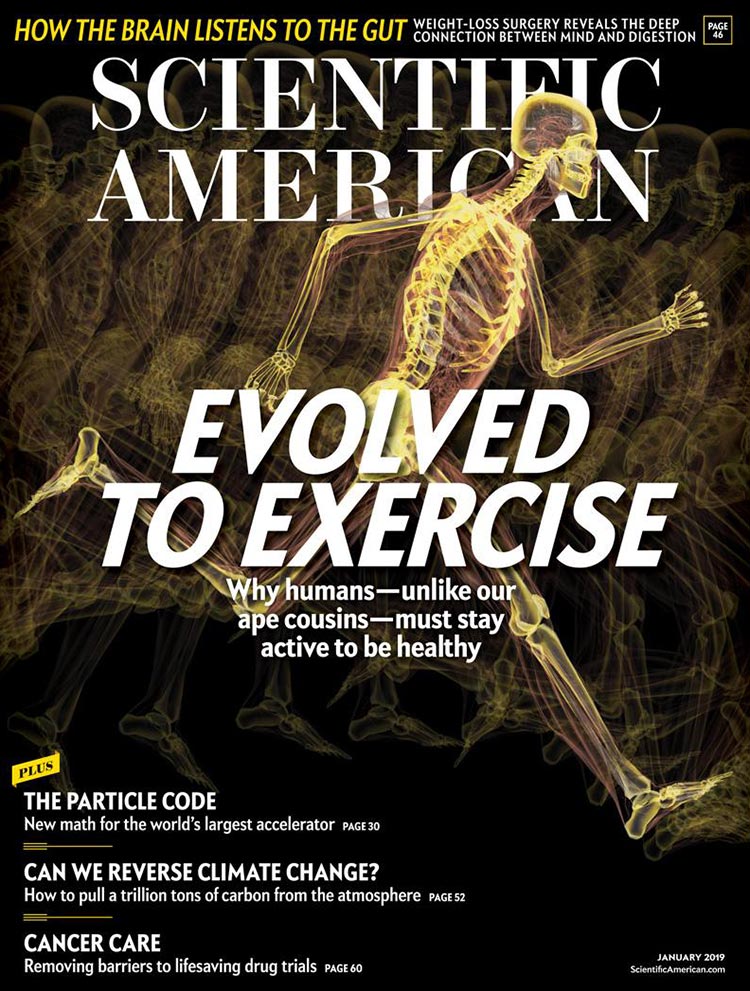

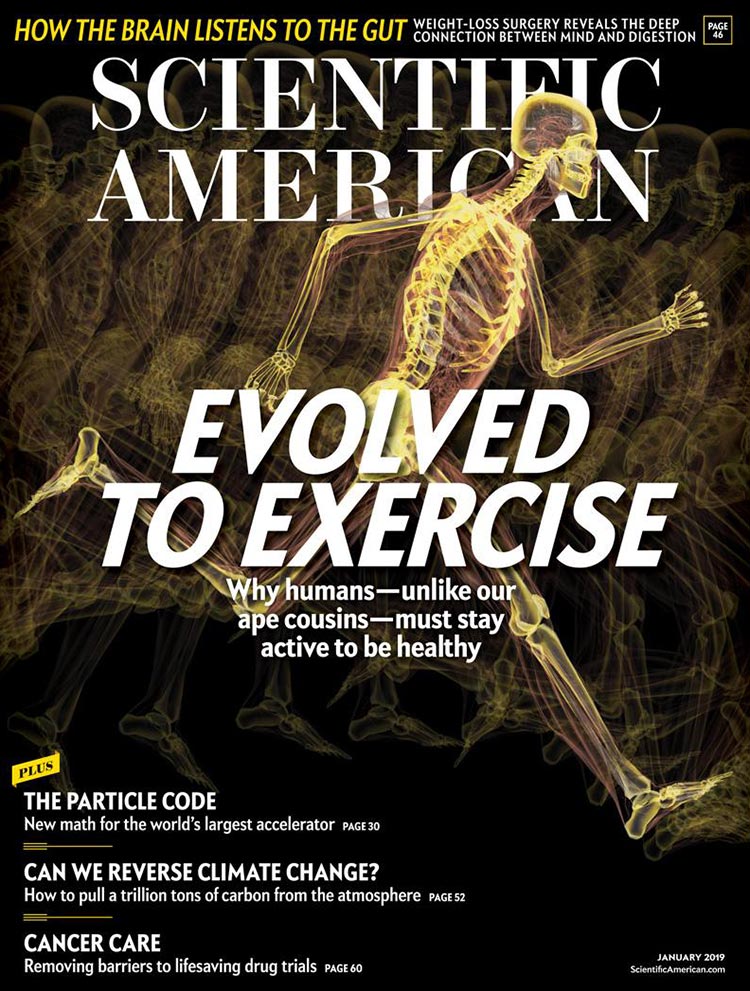

This column was first published in the January 2019 issue of Scientific American.

In the April 2001 issue of Scientific American, I began this column with an entry entitled “Colorful Pebbles and Darwin’s Dictum,” inspired by the British naturalist’s remark that “all observation must be for or against some view, if it is to be of any service.” Charles Darwin penned this comment in a letter addressing those critics who accused him of being too theoretical in his 1859 book On the Origin of Species. They insisted that he should just let the facts speak for themselves. Darwin knew that science is an exquisite blend of data and theory. To these I add a third leg to the science stool—communication. If we cannot clearly convey our ideas to others, data and theory lie dormant.

For 214 consecutive months now, I have tried to communicate my own and others’ thoughts about the data and theory of science as clearly as I am able. But in accordance with (Herb) Stein’s Law—that things that can’t go on forever won’t—this column is ending as the magazine redesigns, a necessary strategy in the evolution of this national treasure, going on 174 years of continuous publication. I am honored to have shared a fleeting moment of that long history, grateful to the editors, artists and production talent for every month I was allowed to share my views with you. I will continue doing so elsewhere until my own tenure on this provisional proscenium ends (another instantiation of Stein’s Law)—many years in the future, nature and chance willing— so permit me to reflect on what I think science brings to the human project of which we are all a part.

Modern science arose in the 16th and 17th centuries following the Scientific Revolution and the adoption of scientific naturalism— the belief that the world is governed by natural laws and forces that are knowable, that all phenomena are part of nature and can be explained by natural causes, and that human cognitive, social and moral phenomena are no less a part of that comprehensible world. In the 18th century the application of scientific naturalism to the understanding and solving of human and social problems led to the widespread embrace of Enlightenment humanism, a cosmopolitan worldview that esteems science and reason, eschews magic and the supernatural, rejects dogma and authority, and seeks to understand how the world works. Much follows. Most of it good.

Human progress, which has been breathtaking over the past two centuries in nearly every realm of life, has principally been the result of the application of scientific naturalism to solving problems, from engineering bridges and eradicating diseases to extending life spans and establishing rights. This blending of scientific naturalism and Enlightenment humanism should have a name. Call it “scientific humanism.”

It wasn’t obvious that the earth goes around the sun, that blood circulates throughout the body, that vaccines inoculate against disease. But because these things are true and because Nicolaus Copernicus, William Harvey and Edward Jenner made careful measurements and observations, they could hardly have found something else. So it was inevitable that social scientists would discover that people universally seek freedom. It was also inevitable that political scientists would discover that democracies produce better lives for citizens than autocracies, economists that market economies generate greater wealth than command economies, sociologists that capital punishment does not reduce rates of homicide. And it was inevitable that all of us would discover that life is better than death, health better than illness, satiation better than hunger, happiness better than depression, wealth better than poverty, freedom better than slavery and sovereignty better than suppression.

Where do these values exist to be discovered by science? In nature—human nature. That is, we can build a moral system of scientific humanism through the study of what it is that most conscious creatures want. How far can this worldview take us? Does Stein’s Law apply to science and progress? Will the upward bending arcs of knowledge and wellbeing reach a fixed upper ceiling?

Remember Davies’s Corollary to Stein’s Law—that things that can’t go on forever can go on much longer than you think. Science and progress are asymptotic curves reaching ever upward but never touching omniscience or omnibenevolence. The goal of scientific humanism is not utopia but protopia—incremental improvements in understanding and beneficence as we move ever further into the open-ended frontiers of knowledge and wisdom. Per aspera ad astra.

read or write comments (1)

A review of It’s Better Than it Looks: Reasons for Optimism in an Age of Fear by Gregg Easterbrook (Public Affairs. February 2018. ISBN 9781610397414.) A shorter version of this review was published in the Wall Street Journal on February 28, 2018 under the title “Why Things Are Looking Up”.

Though declinists in both parties may bemoan our miserable lives, Americans are healthier, wealthier, safer and living longer than ever.

In his 1971 book A Theory of Justice, the Harvard philosopher John Rawls argued that in the “original position” of a society we are all shrouded in a “veil of ignorance” of how we will be born—male or female, black or white, rich or poor, healthy or sick, slave or free—so society should be structured in such a way that laws do not privilege any one group because we do not know which category we will ultimately find ourselves in.

Writing during a time when civil unrest over centuries of injustice was spilling out into the streets in marches and riots, Rawls’ work was as much prescriptive as it was descriptive. But 45 years later, at a 2016 speech in Athens, Greece, President Barack Obama affirmed that a Rawlsian society was becoming a reality: “If you had to choose a moment in history to be born, and you did not know ahead of time who you would be—you didn’t know whether you were going to be born into a wealthy family or a poor family, what country you’d be born in, whether you were going to be a man or a woman—if you had to choose blindly what moment you’d want to be born you’d choose now.” As Obama explained to a German audience earlier that year: “We’re fortunate to be living in the most peaceful, most prosperous, most progressive era in human history,” adding “that it’s been decades since the last war between major powers. More people live in democracies. We’re wealthier and healthier and better educated, with a global economy that has lifted up more than a billion people from extreme poverty.” (continue reading…)

Comments Off on Realizing Rawls’ Just Society

A Response to George Ellis’s Critique of My Defense of Moral Realism

This article appeared in Theology and Science in December 2017.

I am deeply appreciative that University of Cape Town professor George Ellis took the time to read carefully, think deeply, and respond thoughtfully to my Theology and Science paper “Scientific Naturalism: A Manifesto for Enlightenment Humanism” (August, 2017),1 itself an abbreviation of the full-throated defense of moral realism and moral progress that I present in my 2015 book, The Moral Arc.2 As a physicist he naturally reflects the methodologies of his field, wondering how a social scientist might “discover” moral laws in human nature as a physical scientist might discover natural laws in laboratory experiments. It’s a good question, as is his query: “Is it possible to say in some absolute sense that specific acts, such as the large scale massacres of the Holocaust, are evil in an absolute sense?”

Pace Abraham Lincoln, who famously said “If slavery is not wrong, then nothing is wrong,”3 I hereby declare in an unequivocal defense of moral realism:

If the Holocaust is not wrong, then nothing is wrong.

Since Professor Ellis is a physicist, let me approach this defense of moral realism from the perspective of a physical scientist. It is my hypothesis that in the same way that Galileo and Newton discovered physical laws and principles about the natural world that really are out there, so too have social scientists discovered moral laws and principles about human nature and society that really do exist. Just as it was inevitable that the astronomer Johannes Kepler would discover that planets have elliptical orbits—given that he was making accurate astronomical measurements, and given that planets really do travel in elliptical orbits, he could hardly have discovered anything else—scientists studying political, economic, social, and moral subjects will discover certain things that are true in these fields of inquiry. For example, that democracies are better than autocracies, that market economies are superior to command economies, that torture and the death penalty do not curb crime, that burning women as witches is a fallacious idea, that women are not too weak and emotional to run companies or countries, and, most poignantly here, that blacks do not like being enslaved and that the Jews do not want to be exterminated. Why? […]

To continue reading this article, download the PDF.

Download the PDF

Comments Off on Mr. Hume: Tear. Down. This. Wall.

I am optimistic that science is winning out over magic and superstition. That may seem irrational, given the data from pollsters on what people believe. For example, a 2005 Pew Research Center poll found that 42 percent of Americans believe that “living things have existed in their present form since the beginning of time.” The situation is even worse when we examine other superstitions, such as these percentages of belief published in a 2002 National Science Foundation study: (continue reading…)

read or write comments (7)

A review of Robert Wright’s Nonzero: The Logic of Human Destiny.

Humans are pattern-seeking, storytelling animals. We look for and find patterns in our world and in our lives, then weave narratives around those patterns to bring them to life and give them meaning. Such is the stuff of which myth, religion, history, and science are made.

Sometimes the patterns we find represent reality — DNA as the basis of heredity or the fossil record as the history of life. But sometimes the patters are imposed by our minds rather than discovered by them — the face on Mars (actually an eroded mountain) or the Virgin Mary’s image on the side of a glass building in Clearwater, Florida (really an oil stain from a palm tree, since removed to enable the faithful to better view their icon). The rub lies in distinguishing which patterns are true and which are false, and the essential tension (as Thomas Kuhn called it) pits skepticism against credulity as we try to decide which patterns should be rejected and which should be embraced. (continue reading…)

read or write comments (5)