How the brain produces the sense of someone present when no one is there

In the 1922 poem The Waste Land, T. S. Eliot writes, cryptically: Who is the third who always walks beside you? / When I count, there are only you and I together / But when I look ahead up the white road / There is always another one walking beside you.

In his footnotes to this verse, Eliot explained that the lines “were stimulated by the account of one of the Antarctic expeditions [Ernest Shackleton’s] … that the party of explorers, at the extremity of their strength, had the constant delusion that there was one more member than could actually be counted.”

Third man, angel, alien or deity — all are sensed presences, so I call this the sensed-presence effect. In his gripping book, The Third Man Factor (Penguin, 2009), John Geiger documents the effect in mountain climbers, solo sailors and ultraendurance athletes. He lists conditions associated with it: monotony, darkness, barren landscapes, isolation, cold, injury, dehydration, hunger, fatigue and fear. I would add sleep deprivation; I have repeatedly experienced its effects and witnessed it in others during the 3,000-mile nonstop transcontinental bicycle Race Across America. Four-time winner Jure Robic, a Slovenian soldier, recounted to the New York Times that during one race he engaged in combat a gaggle of mailboxes he was convinced were enemy troops; another year he found himself being chased by a “howling band” of black-bearded horsemen: “Mujahedeen, shooting at me. So I ride faster.” (continue reading…)

read or write comments (10)

Evolutionary economics explains why irrational

financial choices were once rational

Since 99 percent our evolutionary history was spent as hunter-gatherers living in small bands of a few dozen to a few hundred people, we evolved a psychology not always well equipped to reason our way around the modern world. What may seem like irrational behavior today may have actually been rational a hundred thousand years ago. Without an evolutionary perspective, the assumptions of Homo economicus — that “Economic Man” is rational, self-maximizing, and efficient in making choices — make no sense. Take economic profit versus psychological fairness as an example. (continue reading…)

read or write comments (21)

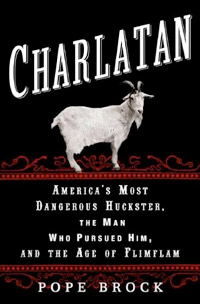

A torrid tale of quackbusting in 1920s America

sheds light on modern medical scares

A review of Pope Brock’s Charlatan. America’s Most Dangerous Huckster, the Man Who Pursued Him, and the Age of Flimflam.

Human cognition has a problem — anecdotal thinking comes naturally whereas scientific thinking does not. The recent medical controversy over whether vaccinations cause autism illustrates this barrier. On the one side are scientists who have been unable to find any causal link between the symptoms of autism and the vaccine’s ingredients. On the other are parents who noticed that shortly after having their children vaccinated autistic symptoms appeared. (continue reading…)

read or write comments (4)

Michael Shermer discusses his book The Mind of the Market as part of the Authors @ Google series.

How did we evolve from ancient hunter-gatherers to modern consumer-traders? Why are people so irrational when it comes to money and business? Dr. Michael Shermer argues that evolution provides an answer to both of these questions through the new science of evolutionary economics. Drawing on research from neuroeconomics, Shermer explores what brain scans reveal about bargaining, snap purchases, and how trust is established in business. Utilizing experiments in behavioral economics, Shermer shows why people hang on to losing stocks and failing companies, (continue reading…)

read or write comments (3)

During his book tour Michael Shermer visited the offices of Reason magazine, who have recently added Reason.TV to their media package, a project helped launched by Drew Carey, who turns out to be a big fan of Skeptic magazine and all things skeptical. In this interview Reason magazine editor Nick Gillespie interviews Shermer on his new book, The Mind of the Market.

read or write comments (6)