An attempted ambush interview turns

into a lesson in patternicity and numerology

On Friday, June 17, a film crew came by the Skeptics Society office to interview me for a documentary that I was told was on arguments for and against God. The producer of the film, Alan Shaikhin, sent me the following email, which I reprint here in its entirety so that readers can see that there is not a hint of what was to come in what turned out to be an attempted ambush interview with me about Islam, the Quran, and the number 19:

Dear Michael!

I am the director of a film crew hired by a non-profit organization, Izgi Amal, from Kazakhstan, which has no connection with the American brat, Borat. We have been working on a documentary film on modern philosophical and scientific arguments for and against God for almost a year. We have been taking shots and interviewed theologians, philosophers and scientists in England, Netherlands, USA, Turkey, and Egypt.

We are planning to finish the film by the end of this year and participate in major film festivals, including Cannes. We will allocate some of the funds to distribute thousands of copies of the film for free, especially to libraries and colleges.

Our crew will once again visit the United States and will spend the rest of June interviewing various people, from layman to artists, from academicians to activists.

Though we are far out there, we know your work and we think that it contributes greatly to the quality of this perpetual philosophical debate. We would like to include perspective and voice in this discussion. We would appreciate if you let us know what days in JUNE would be the best dates to meet you and interview you for this engaging and fascinating documentary film.

Since we are planning to interview about 10 scholars and experts of diverse positions such as atheism, agnosticism, deism, monotheism, and polytheism, it is important to learn all available days in this month of June.

Please feel free to contact us via email or our cell phone numbers, below. If you respond via email and please let us know the best phone number and times to reach you.

Peace,

Alan Shaikhi

In hindsight perhaps I should have picked up on his admission that “we are far out there,” which in fact they turned out to be. Present were Mr. Shaikhin, another gentleman named Edip Yuksel, a couple of film crew hands, and a woman videographer who was setting up all the lighting and equipment. Before we began Shaikhin explained that they were actually filming two projects, and that his colleague (Mr. Yuksel) would be interviewing me after he, Shaikhin, was finished. Yuksel, in fact, was very fidgety and throughout the interview with Shaikhin I could see him out of the corner of my eye feverishly taking notes and fiddling around with books whose titles I could not see.

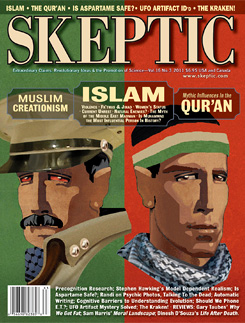

Shaikhin’s interview, in fact, included mostly standard faire questions for such documentaries: Do I think there’s a conflict between science and religion?, What do I think about this and that argument for God’s existence?, Why do I think people believe in God?, etc. He was unfailingly polite and professional. Toward the end he did make some vague reference to Islam and our cover story of Skeptic on myths about the Islamic religion (the myth of the Middle East Madman, the myth of the 72 virgins, etc.), but I begged off answering anything about Islam because I haven’t studied it much nor have I read the Quran.

My first clue that the interview was about to take a sharp right turn came when Shaikhin acted shocked that I would edit an issue of Skeptic on Islam without myself having read the Quran. I explained that I write very few articles in Skeptic and that my job as editor is to find writers who are experts on a subject, which was, in fact, the case with this issue when our Senior Editor Frank Miele interviewed the University of California at Santa Barbara Islamic scholar R. Stephen Humphreys. Nonetheless, Shaikhin continued to act surprised, repeating “you mean to tell me that you edited a special issue of Skeptic on Islam and haven’t read the Quran?” I again explained that editors of magazines are not always (or ever) the world’s leading expert on the topics they publish, which is the very reason for contracting with experts to write the articles for magazines.

With this first part of the interview completed, Edip Yuksel leaped up out of his chair like a WWF wrestler charging into the ring for his big match. He grabbed a chair and pulled it over next to mine, asked for a bottle of water for the match, and instructed the videographer to widen the shot to include him in the interview. Only it wasn’t an interview. It was a monologue, with Yuksel launching into a mini-history of how he wrote Carl Sagan back in 1992 about the number 19 (he didn’t say if Sagan ever wrote back), how Carl had written about the deep significance of the number π (pi) in his science fiction novel Contact, how he is a philosopher and a college professor who teaches his students how to think critically, and that he is a great admirer of my work. However (you knew this was coming, right?), there is one thing we should not be skeptical about, and that is the remarkable properties of the number 19 and the Quran.

At this point I had a vague flashback memory of the Million Man March in Washington, D.C. and Louis Farrakhan’s musings about the magical properties of the number 19. The transcript from that speech confirmed my memory. Here are a few of the numerological observations by Farrakhan that day in October, 1995:

There, in the middle of this mall is the Washington Monument, 555 feet high. But if we put a one in front of that 555 feet, we get 1555, the year that our first fathers landed on the shores of Jamestown, Virginia as slaves.

In the background is the Jefferson and Lincoln Memorial, each one of these monuments is 19 feet high.

Abraham Lincoln, the sixteenth president. Thomas Jefferson, the third president, and 16 and three make 19 again. What is so deep about this number 19? Why are we standing on the Capitol steps today? That number 19—when you have a nine you have a womb that is pregnant. And when you have a one standing by the nine, it means that there’s something secret that has to be unfolded.

I want to take one last look at the word atonement.

The first four letters of the word form the foundation; “a-t-o-n” … “a-ton”, “a-ton”. Since this obelisk in front of us is representative of Egypt. In the 18th dynasty, a Pharaoh named Akhenaton, was the first man of this history period to destroy the pantheon of many gods and bring the people to the worship of one god. And that one god was symboled by a sun disk with 19 rays coming out of that sun with hands holding the Egyptian Ankh – the cross of life. A-ton. The name for the one god in ancient Egypt. A-ton, the one god. 19 rays.

This is a splendid example of what I call patternicity: the tendency to find meaningful patterns in both meaningful and meaningless noise. And Edip Yuksel launched into a nonstop example of patternicity when he pulled out his book entitled Nineteen: God’s Signature in Nature and Scripture (2011, Brainbow Press; see also www.19.org) and began to quote from it. To wit…

-

The number of Arabic letters in the opening statement of the Quran, BiSMi ALLaĤi AL-RaĤMaNi AL-RaĤYM (1:1) 19

-

Every word in Bismillah… is found in the Quran in multiples of 19

-

The frequency of the first word, Name (Ism) 19

-

The frequency of the second word, God (Allah) 19 x 142

-

The frequency of the third word, Gracious (Raĥman) 19 x 3

-

The fourth word, Compassionate (Raĥym) 19 x 6

-

Out of more than hundred attributes of God, only four has numerical values of multiple of 19

-

The number of chapters in the Quran 19 x 6

-

Despite its conspicuous absence from Chapter 9, Bismillah occurs twice in Chapter 27, making its frequency in the Quran 19 x 6

-

Number of chapters from the missing Ch. 9 to the extra in Ch. 27. 19 x 1

-

The total number of all verses in the Quran, including the 112 unnumbered Bismillah 19 x 334

-

Frequency of the letter Q in two chapters it initializes 19 x 6

-

The number of all different numbers mentioned in the Quran 19 x 2

-

The number of all numbers repeated in the Quran 19 x 16

-

The sum of all whole numbers mentioned in the Quran 19 x 8534

This goes on and on for 620 pages which, when divided by the number of chapters in the book (31) equals 20, which is one more than 19; since 1 is the cosmic number for unity, the first nonzero natural number, and according to the rock group Three Dog Night the loneliest number, we subtract 1 from 20 to once again see the power of 19. In fact, 19 is a prime number, it is the atomic number for potassium (flip that “p” to the left and you get a 9), in the Baha’i faith there were 19 disciples of Baha’u’llah and their calendar year consists of 19 months of 19 days each (361 days), and it’s the last year you can be a teenager and the last hole in golf that is actually the clubhouse bar. In point of fact we can find meaningful patterns with almost any number:

-

99: names of Allah; atomic number for Einsteinium; Agent 99 on TV series Get Smart

-

40: 40 days and 40 nights of rain; Hebrews lived 40 years in the desert, Muhammad’s age when he received the first revelation from the Archangel Gabriel and the number of days he spent in the desert and days he spent fasting in a cave

-

23: The 23 enigma: the belief that most incidents and events are directly connected to the number 23

-

11: sunspot cycle in years, the number of Jesus’s disciples after Judas defected

-

7: 7 deadly sins and 7 heavenly virtues; Shakespeare’s 7 ages of man, Harry Potter’s most magical number

-

3: number of dimensions; number of sides of a triangle, the 3 of clubs—the forced pick in one of Penn & Teller’s favorite card tricks

-

1: unity; the first non-zero natural number, it’s own factorial and it’s own square; the atomic number of hydrogen; the most abundant element in the universe; Three Dog Night’s song about the loneliest number

-

π (pi): a mathematical constant whose value is the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter, or 3.14159…. Make of this what you will, but Carl Sagan did elevate π to significance at the end of Contact:

The universe was made on purpose, the circle said. In whatever galaxy you happen to find yourself, you take the circumference of a circle, divide it by its diameter, measure closely enough, and uncover a miracle—another circle, drawn kilometers downstream of the decimal point. In the fabric of space and in the nature of matter, as in a great work of art, there is, written small, the artist’s signature. Standing over humans, gods, and demons, subsuming Caretakers and Tunnel builders, there is an intelligence that antedates the universe.

At this point in the filming process I interrupted Yuksel and told Shaikhin that the interview was over, that he could use the footage from the first part of the interview but not this monologue mini-lecture that was an undisguised attempt to convince me of the miraculous properties of the number 19. I didn’t sign any waiver or permission to use any of the footage shot that day, but just in case I was relieved when the videographer came to me in private to apologize and explain that she had nothing to do with the rest of the crew, that she was just hired to do the filming, and that after I had put an end to the interview she stopped filming.

At some point I asked Edip why he felt so compelled to convince me of the meaningfulness of the number 19 in the Quran, when I told him that I haven’t read the Quran and hold that all such numerological searches are nothing more than patternicity. The impression I got was that if he could convince a professional skeptic then there must be something to the claim. I asked him what other Islamic scholars who have read the Quran think of his claims for the number 19, and he told me that they consider him a heretic. He said it as a point of pride, as if to say “the fact that the experts denounce me means that I must be on to something.”

P.S. Edip Yuksel did strike me as a likable enough fellow who seemed genuinely passionate about his beliefs, but there was something a bit off about him that I couldn’t quite place until I was escorting him out of the office and he said, “I see you are a very athletic fellow. Can I show you something that I learned in a Turkish prison?” With scenes from Midnight Express flashing through my mind, I muttered “Uhhhhhh… No.”

Patternicity Challenge to Readers

As a test—of sorts—I would like to hereby issue a challenge to all readers to employ their own patternicity skills at finding meaningful patterns in both meaningful and meaningless noise with such numbers and numerical relationships, both serious and lighthearted, related to the number 19 or any other number that strikes your fancy. Post them here and we shall publish them in a later feature-length article I shall write on this topic.