The conjunction of reading Christopher Hitchens’ new memoir, Hitch 22, and the news of his treatment for esophageal cancer, reminded me that I should share my (admittedly limited) experiences of dining (and drinking) with one of the greatest literary masters and creative thinkers of our age.

First, I’m half way through listening to the unabridged audio book of Hitch 22, which I wholeheartedly recommend because Christopher reads it himself in that inimitable classically-educated British accent with his style of flowing quiet narrative punctuated with occasional bursts of accented emphasis. In other words, Hitchens sort of mumbles modestly along, then suddenly his voice rises into crystal clarity when he wants you to get the point hard and fast. Hitch 22 is a literary masterpiece, an absolute joy to listen to. I’ll leave it to his literary/politico peers to critique the ideas within (see, for example, the latest issue of The New York Review of Books with Ian Buruma’s review, as well as David Horowitz’s insightful analysis of Hitchens’ evolving political beliefs.

Although I’m a self-professed libertarian (fiscally conservative and socially liberal), I’m really not much of a politico or social commentator, especially when it comes to foreign affairs, about which I am woefully ignorant compared to Hitchens’ vast database he has accumulated throughout his many travels abroad. So I’m just enjoying the ride listening to Christopher’s many amusing stories. (One funny anecdote is when Hitchens explained that in an early writing job for a publication, his editor said something to him that, as he explained it, made it simply impossible for him to continue employment there. It turned out that the editor told him “you’re fired.”)

My intersection with Hitchens is through our mutual concern about the influence of religion on science. Hitchens, of course, has many other worries about the effects of religious beliefs on political, economic, and social conditions around the world (particularly the Middle East), but he was kind and generous enough to provide a back-jacket blurb for my book, Why Darwin Matters ($10 hardcovers at Shop Skeptic), and noted in his letter to me that contained said blurb that he had found a couple of minor errors in the book, adding parenthetically (in case I missed it) that this meant that he did, indeed, actually read the book. (In the book publishing business it is common practice for authors who are friends and colleagues to blurb each other’s books, and sometimes I suspect this means that the blurb was generated based on a cursory scan of the manuscript. To his credit and energy—considering how many blurb requests he must receive—Christopher really did read the entire manuscript.

I first met Christopher in Hollywood in 1997 at a preview showing of the film FairyTale: A True Story, starring Harvey Keitel as Harry Houdini and Peter O’Toole as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, which recounted the story of the two giants’ intersection over the fake fairy photographs that Doyle fell for and Houdini did not. Hitch and I had dinner (well lubricated with adult beverages) before the preview, and although I was a bit distressed at the ending of the film that implied that fairies may actually be real (after showing that Doyle was duped), I rather enjoyed the film. Christopher’s review in Vanity Fair, which included a thoughtful and much appreciated endorsement of the Skeptics Society and Skeptic magazine, was much deeper and more insightful than anything I thought of during the viewing. Even though I’m a professional skeptic, for some reason when I watch a film I willing suspend disbelief in order to enjoy the process, and this sometimes interferes with my critical thought processes.

A decade later, in 2007, as I was meandering through the sensory overloaded Las Vegas airport on my way to The Amazing Meeting 5 and Freedom Fest, both conferences at which Hitchens and I were speaking, we encountered each other in search of our respective limo drivers, so we ended up sharing a ride to the hotel. Checking in early (it was around 11:00 am) our rooms were not yet ready, so Hitch suggested that we put the time to good use at the bar. Before. Noon. So there we were, my nursing a Corona with lime for as long as I could socially get away with it while Hitchens ordered a Johnny Walker Black, a red wine, and a bottle of water to mix with JWB in what appeared to be a well-choreographed routine. A couple of rounds later Hitch seemed completely unfazed, while my empty-stomach imbibing on that single beer left me feeling less than adequate to keep up with the conversation. (Hey, when you drink with a professional come prepared. I didn’t have the training miles I’m afraid.) When the bill came I had the singular honor of buying Christopher Hitchens’ drinks because (1) his wallet was in his baggage with the bellman, and (2) the room keys were not yet activated to put it on his room. I didn’t mind a bit—blurb reciprocity and all that, you know.

After hammering down two rounds of the Hitch Mix, Christopher was nearly (but not quite) ready for his noon-time luncheon speech, so he ordered a third round to go. At the podium where Hitch stood, before him were a glass of whiskey, a red wine, and a bottle of water. (Just as we cyclists always ride with water bottles filled with fluid replacement drinks, Christopher apparently never speaks without his Hitch Mix to top off his energy needs.) I can’t for the life of me remember what his speech was about (politics I’m sure) but I recall that Hitchens was extemporaneous, clever, and worldly.

That night the host of Freedom Fest, Mark Skousen, invited Christopher and myself to join a group of Big Thinkers at an exclusive (and quite expensive I’m sure) dinner at one of the posher restaurants in Las Vegas (no prices on the menu is all you need to know). Even though everyone at the table was someone of some import and standing, it was clear throughout the evening that Hitch was Sol and we were his orbiting planets gathering up the warmth of his verbal rays. He told stories—lots and lots of stories—about his travels, his encounters with names we would all surely know, and especially about his ideological battles with this and that ideologue. Other people’s comments were, for the most part, stimulants for another Hitch story. I can see why some people might find that this rubs them the wrong way, but for some reason—at least for me—that was how it should have been. If you invite Christopher Hitchens to your dinner, expect to be entertained, and the more the waiter poured expensive wine, the more histrionic Hitchens became, until four hours and who-knows-how-many-drinks later I detected a slight slowing of his verbal and cognitive skills…so there are limits after all.

The next time I saw Hitch was at a party in Washington D.C., when I was touring for the release of my book, The Mind of the Market ($8.95 hardcovers at Shop Skeptic). Reason magazine kindly arranged for a book party at a bar and restaurant that was so crowded and so loud that it was physically uncomfortable. After an obligatory drink and a few stories to entertain the troops, Hitchens leaned in and said “Michael, why don’t we retire to a restaurant down the street where they know me?” Exiting the cacophony, we walked a few blocks to what turned out to be one of Hitches’s regular haunts. “The usual place, Mr. Hitchens?” the maitre’d inquired. We were escorted to a quite corner of the restaurant, where Hitch positioned himself to be able to scan the room, and soon we were joined by his wife and an occasional passerby who recognized him and dropped in for a story (and drink) or two.

Shortly after the waiter took our drink orders (“the usual?” was all Hitch needed to hear, to which he nodded affirmatively), the Hitch Mix was on the table, followed by a fabulous dinner and, of course, lots of stories, none of which were repeated from my previous dinner (at least that I could remember—I too imbibed). After a couple hours at the restaurant, Hitch invited me to his home not far from the restaurant, where I was treated to a visual delight: mountains of books, oceans of books, a sea of books—pick your geographical metaphor. As the recipient myself of bound galleys and newly published volumes sent to Skeptic magazine for review, I know how quickly a mass accumulates on my desk that then migrates to the floor and eventually peaks above the desk again. But these are just science books. As a literary polymath Hitch receives books for review from virtually every category in the Dewey Decimal System. And he actually seems to read the books he reviews.

But the library is not where we adjourned for the evening. It wasn’t long before I found myself at a rectangular table in the dining room chockablock full of whiskey bottles from around the world. I’m not a whiskey connoisseur so I couldn’t tell you the brand names, but even a teetotaler like me could tell from the labels and bottle designs that here was a collection of the very best whiskeys that money can buy from all over the world, and I suspect that Hitch didn’t have to buy many of them, since such gifts seem to naturally flow his way. So I sampled and sipped and sauced my way into a late-night bliss that I paid for dearly the next day. I think I had an interview for an early morning television show, but I honestly don’t remember because I barely recall even having a next day.

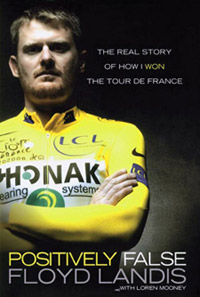

Was it worth it? I once had an opportunity to ride my bike 50 miles on a fundraising event next to the great Belgian champion Eddy Merckx, considered the greatest cyclist of all time. I was so nervous about crashing and taking him down that I just concentrated on the bumper in front of us that we were drafting behind at 30 miles per hour. But just the experience of riding side by side with one of the greatest athletes to ever grace the planet was enough for me. That’s how I felt drinking and dining and delighting in the presence of Christopher Hitchens.